This exhibition brings together works by eight Chinese artists which respond to the complexities of the Chinese written language. Whether exposed at an early age to the practice of calligraphy or simply conversant with its basic premises, none of the artists here, with the exception of Gu Wenda, work in the traditional medium of ink and brush on paper. Instead, we find calligraphy on silk and canvas supplemented with video (Yang Jiechang), burnt into xuan paper (Wang Tiande), executed by flashlight (Qiu Zhijie), reduced to one bit form and silkscreened on panel (Feng Mengbo), created from grape tendrils and photographed (Cui Fei) and finally painted in water on stone (Song Dong). For the most part the emphasis is on form rather than content and on unorthodox methods of execution, Qiu Zhijie choosing to write in reverse and from left to right rather than from right to left and top to bottom as is normally the case. Hong Lei uses ink not to write or depict a mountainous landscape but to create a miniature, three-dimensional mountain.

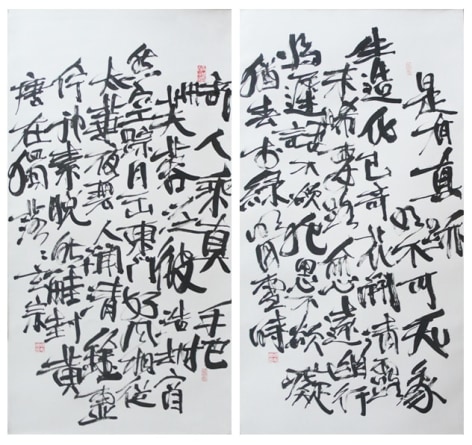

Gu Wenda, Yang Jiechang and Wang Tiande were all conversant with ink painting and calligraphy from an early age but developed practices that refer in strikingly different ways to the traditional understanding of this quintessential Chinese form of expression. In his extensive Pseudo-Character series (1983-87) Gu deprived characters of their meaning by reversing the order of the component parts, executing them upside down etc. Yang Jiechang chose to explore the character of the medium itself in his Layers of Ink series but has also produced a number of calligraphic works in which, as in I Often do Bad Things, he often uses banal statements and sometimes writes in English. Wang Tiande adopts a more nuanced approach. In the ongoing Digital series, he continues to develop a technique he discovered by accident when burning ash from a cigarette fell on a sheet of rice paper creating forms that resembled Chinese characters and landscape forms. Typically, a landscape or calligraphic inscription executed in ink on paper and representative of tradition is covered with a sheet of translucent xuan paper into which forms reminiscent of the under- painting are burned. Glimpses of tradition can be seen through the contemporary scrim.

Qiu Zhijie and Feng Mengbo are also strongly attracted to classical Chinese culture although seen from different perspectives. Qiu is a gifted calligrapher who likes to explore unconventional methods as in his series of calli-photographs in which he combines two of his principal interests, photography and calligraphy made by using a flashlight instead of a brush. He also needed to write in reverse in order to create legible images in the photographic prints. After what Feng Mengbo, China’s foremost new media artist, has referred to as “a decade-long romance with the computer,” he has recently returned to painting. For the Yi Bite paintings dating from 2010, he turned to images from the Jieziyuan Huazhuan (The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting) and randomly selected groups of characters from Buddhist texts. Reduced to one - bit form – the smallest amount of information possible for a computer image – and silkscreened onto wooden panels covered with silver leaf, these harsh black forms contrast in every respect with their source of inspiration.

Cui Fei and Song Dong owe least to traditional calligraphy since Cui works with twigs and thorns and Song Dong, although he uses a brush, does not use ink. Cui’s work encompasses painting, photography and installations but uniting them all is a deep love of nature which she finds in materials such as “tendrils, leaves and thorns composing a manuscript symbolizing the voiceless messages in nature that are waiting to be discovered and to be heard.” For Song Dong calligraphy is a private activity that does not result in tangible results capable of being admired by connoisseurs. In his celebrated Water Diary (1995 to the present day), he commits his most intimate thoughts to water on stone on a daily basis. Recorded only in photographic form, Song Dong’s extended calligraphic practice may be seen as both a comment on the evanescence of life (a classic Buddhist theme) and the constraints of living in China where privacy is in short supply and committing thoughts to paper can be a dangerous activity.

Song Dong practices calligraphy without using ink. Hong Lei, on the other hand, uses ink as a sculptural material without diluting it or using a brush. In his Ink Mountain he uses ink to create a miniature mountain, a discreet homage to the material used by Chinese painters and calligraphers from the earliest times until today.