Chambers Fine Art is pleased to announce the opening on January 24, 2018 of Cao Yi, Li Qing, Yi Xin Tong, and Zhao Zhao: Adrift. The exhibition examines the current urban landscape of China with megacities unimaginable in scale just a few decades ago, through the work of four young artists intimately familiar with this period of rapid change. The transformation of China in the last thirty years has been well-documented, with vast migrations from the country into the cities, and the ecological crisis that has emerged as a result of all this. In the 1990s many artists used this material in their works, for example Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen, Wang Jianwei, Zhang Dali – but for the younger generation who did not have direct experience of this upheaval, the new realities of contemporary urban life in China have very often become background noise that they barely notice. The four artists presented in this exhibition therefore do not directly reference the urban transformation of China – rather, their experiences growing up and now working within this environment provide a set of viewpoints that is unique to their generation.

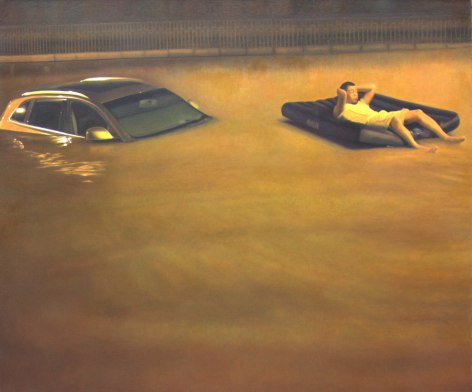

Zhao Zhao got to know the topography of Beijing extremely well during the many months he worked on Ai Weiwei’s Beijing videos of the early 2000s, but his references are indirect, such as the exceptional rainstorm in when he painted himself relaxing on an inflatable mattress, floating down the flooded streets of Caochangdi. Based on an actual event, Rain is also the title of a video that Zhao Zhao filmed during the flooding that occurred in Beijing on July 21, 2012. The artist found an inflatable mattress, upon which he floated as he documented the flooded city. As a counterpoint to Rain, on view are a pair of Zhao Zhao’s Sky paintings, representing the artist’s commentary on the heavily polluted air in Beijing. The swirling, turbulent blue and white atmosphere he depicts also serves as a metaphor for the constantly shifting politics of Beijing.

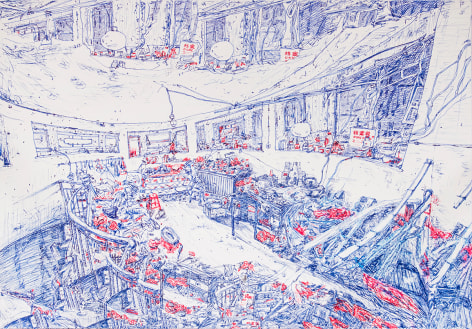

Yi Xin Tong’s project uses thematic material that relates to the influx of rural migrants into urban centers but adds an element of fantasy. His subject is a former zoo in his hometown province within Lu Shan National Park, now a UNESCO Heritage site. The popular zoo closed down decades ago, and in the ensuing years local people and migrants have moved into and out of the animals’ former living quarters, leaving traces of their lives in the buildings. The artist imagines a modern day myth:

“Over time, the inhabitants gradually became infected with the instincts and even the souls of the animals that lived there before. Paws, fangs, and wings grew out of their bodies… Eventually, when they fully transformed into birds and beasts, they escaped from the cages and rushed into the mountains. Some say that instead of turning into animals, they became enlightened immortals…”

Alongside photographs and drawings, a video completes the installation: in front of the now demolished “New Peacock Pavilion”, an old woman’s almost choreographed movements herding her chickens seem to illustrate the odd, strained and yet comedic relationship between human society and nature.

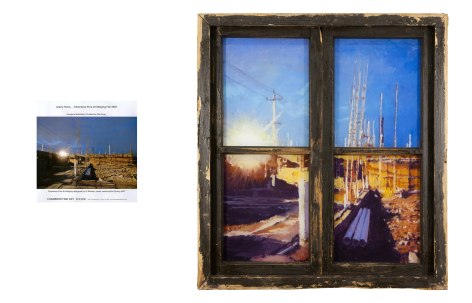

Like Song Dong, Li Qing uses parts of demolished houses, windows and door frames, but in witty tableaux rather than as commentary on the destructiveness of urban renewal. The window frames become picture frames. In his “blow-up” series, first shown at the 9m2 Museum (Goethe Institute, Shanghai), he takes magazine ads and exhibition posters related to Chinese contemporary art from the mid-2000s and enlarges several of them into oil paintings set behind his window frames. The images refer to the sudden explosion of interest in Chinese contemporary art during those years, when the art scene as a whole became an object of desire so excessively amplified by the media that it obscured the original significance of the artworks themselves. Li Qing has transformed one section of the gallery into a faux bathroom, from which the viewer looks out through the ‘windows’ onto this peculiar moment of recent history.

Cao Yi’s paintings are exquisite renderings of a dystopian environment – housing projects with cracked walls and peeling paint, corporate offices, and omnipresent surveillance cameras found in Beijing and every major city in China. The acrylic on paper works are somewhat reminiscent of architectural elevations, but rendered with intense passages of color, often depicting specific details in the foreground: fences, bricks, and vegetation. Among his static portrayals of everyday life in Beijing, there is a small painting of a window with the curtains drawn, with what appears to be glimpses of the buildings outside. Even without the physicality of reclaimed window frames, the piece achieves a feeling similar to Li Qing’s ‘windows’, of being in a small space, looking out upon a foreign, yet familiar landscape. In contrast, the larger works by Cao Yi turn the perspective around completely, with grids of opaque, non-descript windows and buildings leaving the viewer to wonder if there is anyone on the inside.