Chambers Fine Art is pleased to announce a new online exhibition featured exclusively on the ADAA Member Viewing Rooms entitled Guo Hongwei: Among the Masses. Since Things, his first exhibition at Chambers Fine Art in 2009, Guo Hongwei’s primary focus has been on painting although in The Great Metaphorist in 2014 he adopted a multi-media approach including video for a metaphorical exploration of the daily commute between his home and studio. In spite of this temporary diversion and occasional ventures into installation, he has continued to produce a varied group of paintings and watercolors in which manmade objects and materials from the natural world are transformed by his innovative handling of watercolor and unusual combinations of different pigments and media in his oil painting. Guo’s watercolors were the subject of his New York solo exhibition Pareidolia at Chambers Fine Art this past March; unfortunately, the exhibition was cut short after only being open for one week, due to the city-wide lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

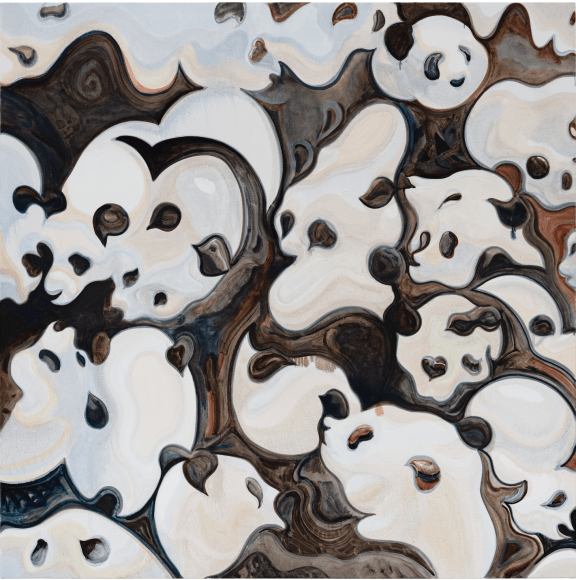

The paintings assembled in the virtual exhibition Among the Masses, conceived and executed during the COVID-19 pandemic, are a striking departure from the watercolors that were shown in New York. Executed in oil on canvas, the works are a thoughtful development of ideas concerning subject matter and technical approaches to painting that have long characterized Guo’s work. Prior to 2009, the thematic content of Guo’s painting had been highly personal, much of it derived from family snapshots. For the greater part of the next decade he favored inanimate subject matter, for example inconsequential objects selected from the clutter in his studio or random images selected from the internet. The culmination of this approach occurred in 2017 with paintings such as The Gate, which at first glance appears to be an eccentric abstraction although in fact it is based on a plastic walker used by his young son while learning to walk. Simultaneously, he began selecting images he found online that incorporated human or animal forms, specially the panda, that provided opportunities for developing the full range of the painterly skills that he had acquired while studying at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute.

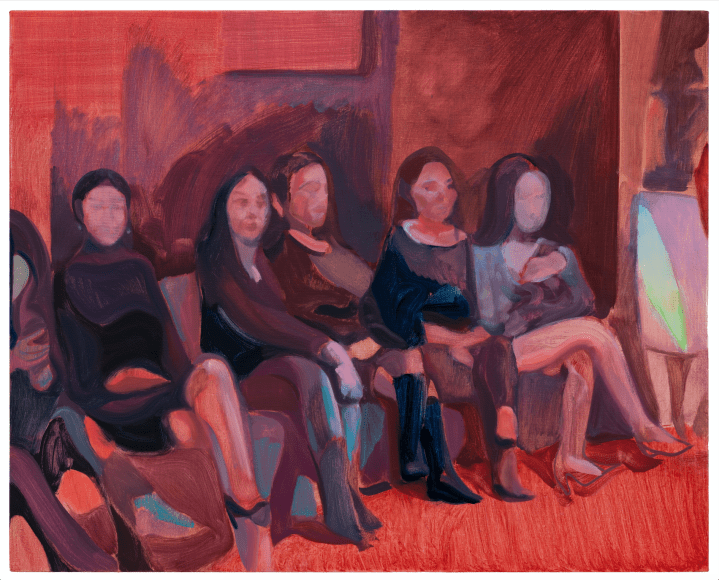

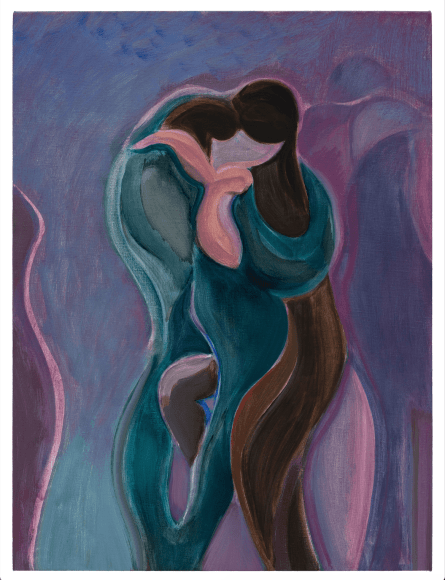

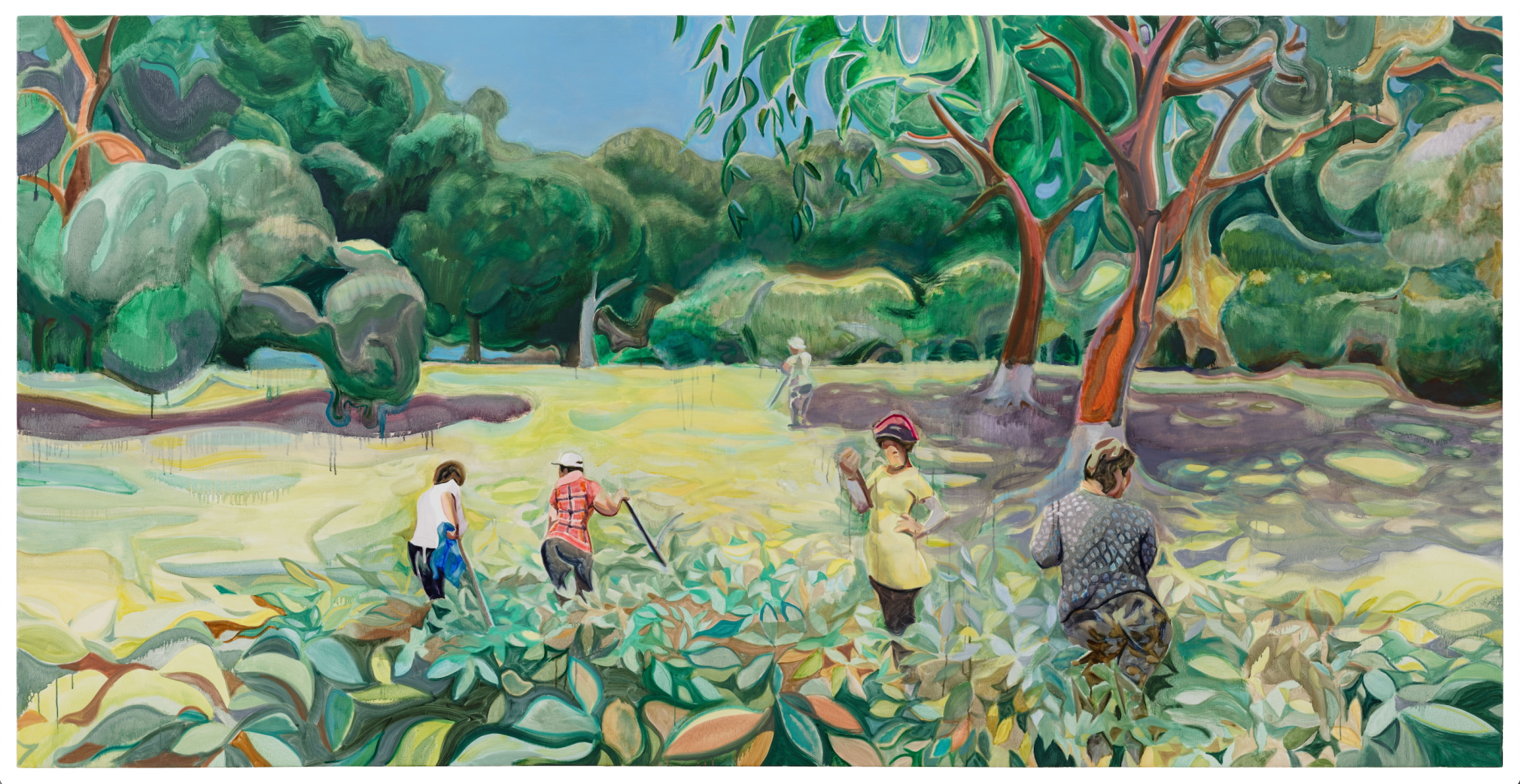

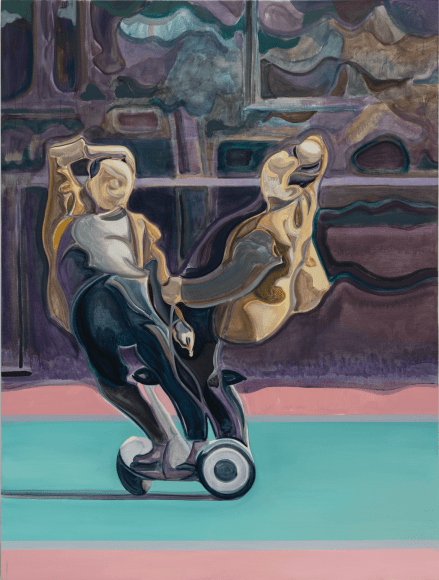

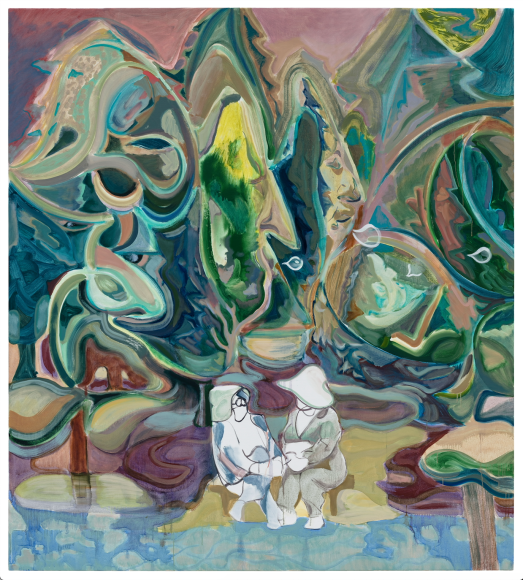

The individual works may be divided into two basic categories, depending on whether the source of inspiration was located online or offline. Even before the pandemic Guo was a devotee of Kuaishou, a video-sharing app wildly popular among young people in China. Viewing himself as a researcher whose aim is to give as broad a view as possible of life in China during the pandemic, he refuses to prioritize among those he finds online he and those he experiences and those he photographs himself. Typical of the first group are Laughing at this World and The Master Practitioner, both inspired by an older man who, lost in his own world, danced solo on a Segway and achieved instant ‘viral’ fame on the Kuaishou platform. In the second group Spring Conversation and the related works, The Dance of Sha and The Love of Sha, are derived from Guo’s own experience, an early morning visit to Tiantan Park where he saw two elderly ladies conversing and a visit to a dance-for-hire club in southwest China, popularly known as “sand dance” clubs in reference to the potential for subdued eroticism during the brief encounters between professional ballroom dancer and client.

At this stage in his career Guo has adopted a new role, that of the contemporary history painter although he does not focus on heroic events, rather the opposite. After a decade of experimenting with different approaches to painting on paper or canvas, he has now come to the realization that it is impossible for a painter of his generation to forget everything that has been done in the past. He has said that he is now more open to his unconscious, and recognizes that every time he applies brush to canvas, the resulting mark might refer to traditional Chinese painting, to Western Old Masters, to manga, or naive art. Once assembled, he believes, they become evidence of his own distinctive personality.