Chambers Fine Art is pleased to announce the opening on March 7 of Taca Sui: Grotto Heavens. This will be the artist’s third solo exhibition at the gallery. In the five years since his first exhibition, Odes (2013), Taca has traveled extensively throughout China in search of remote locations that resonate in Chinese history through their association with important religious and philosophical traditions. In Odes, he presented a body of work that was inspired by the ancient poetic heritage of China, specifically the Book of Odes (Shi Jing). Laden down with his heavy equipment, like pioneering photographers of the nineteenth century he traveled to remote locations that were associated with these ancient lyrics, photographing landscapes and evocative details that were remarkable for their poetic intensity.

During the next two years in preparation for the exhibition Steles: Huang Yi Project (2015), his theme was the stone steles that have played such a crucial role in the documentation of the history of China. Here he was inspired by the late Qing dynasty imperial bureaucrat Huang Yi (1744 – 1802) who in his leisure time was also a dedicated amateur archaeologist. In planning his own trips, Taca consulted Huang Yi’s diaries, Diary on Visiting Steles near Mount Song and the Luo River and Diary on Visiting Historical Steles from Jining to Tai’an.

In 2017, Taca embarked on yet another extended journey, this time in search of the grotto-heavens that with the Five Great Mountains occupy a primordial position within the sacred geography of China. Described by scholar Franciscus Verellen as “places of refuge, initiation, and of transcendental passage, paradisial microcosms,” these sacred sites (dongtian) were particularly important in Daoist ritual and cosmography, and were first mentioned in the revelations of Shangqing around 360 CE. They were organized systematically in the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) by Sima Chengzhen (647-735) and Du Guangting (850-933) and are now divided into two categories, the ten greater grotto heavens and the thirty - six lesser grotto heavens.

Now that he has learnt how to drive, Taca was away from his home in Beijing for many months, visiting the Mausoleum of the King of Chu, Songshan Mountain, and Zhongtiao Mountian Wangwu in Henan province; Shangluo, Taibai Mountain, Qinling, Ankang and Hangzhong in Shaanxi province; and Yichang, Shiyan, Shennongjia, and Enshi in Hubei Province. Two more expeditions are planned in the future to complete his survey.

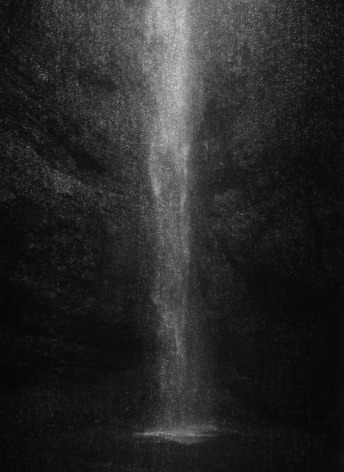

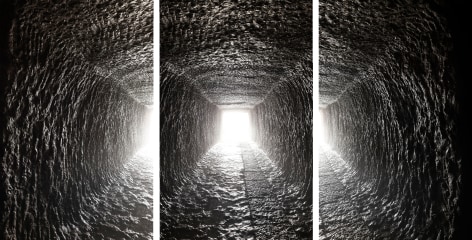

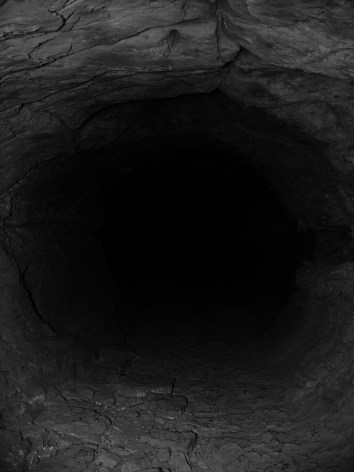

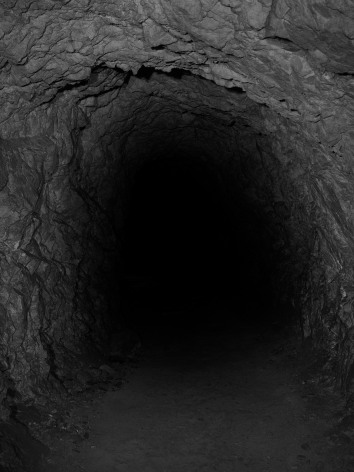

The exhibition is divided into two parts, one of which is devoted to the caves in which the grottoes are situated and the other to a new iteration of his Steles project. In the black and white photographs that convey the poetry of the caves, the mysterious interiors suggest the sense of awe they inspired in the pilgrims who visited them in full expectation of achieving powerful insights into another world. Using a contemporary analogy, Taca has compared these grotto heavens to wormholes, passageways through space-time that theoretically would permit journeys as mysterious as those achieved in grotto-heavens. Presented in a smaller scale at one end of the gallery, Taca revisits his Steles: Huang Yi Project, this time focusing on one specific image from the original set of photographs, entitled Stele by Zheng Jixuan. Dividing the image into 35 individual sections, each part is presented as a separate photograph, appearing as semi-abstracted landscapes themselves, or ‘bird’s eye view’ images of mountain terrain.

Among contemporary photographers of his generation Taca is unusual in his overriding interest China as it used to be, not as it exists today. There are virtually no references to the present or even the recent past, the exceptions being the occasional appearance of forlorn relics of past devotional practices left behind in these caves. Far from being a documentary photographer, however, bringing back reports from remote areas, he uses photography as a way of establishing a rapport between his own unique vision and the sparse evidence he finds in his travels of long-gone and largely forgotten practices, far from the concerns of the great majority of the inhabitants of a newly prosperous China. His preference for the unassuming and the overlooked, the acceptance of impermanence, can be compared with the concept of wabi-sabi which played such an important role in the development of Japanese aesthetics.

Taca’s work has entered the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Asia Pacific Museum in Pasadena, CA.