Chambers Fine Art is pleased to announce the opening on February 11, 2016 of Fu Xiaotong: Land of Serenity. Born in Shanxi in 1976, Fu Xiaotong received her BA in Fine Arts from the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, Tianjin in 2000 and later studied at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing from which she graduated in 2013. It was while she was at the Academy that she developed a strong affinity for handmade Xuan paper that has been used within China since the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and is still the preferred support for traditional brush and ink painters and calligraphers.

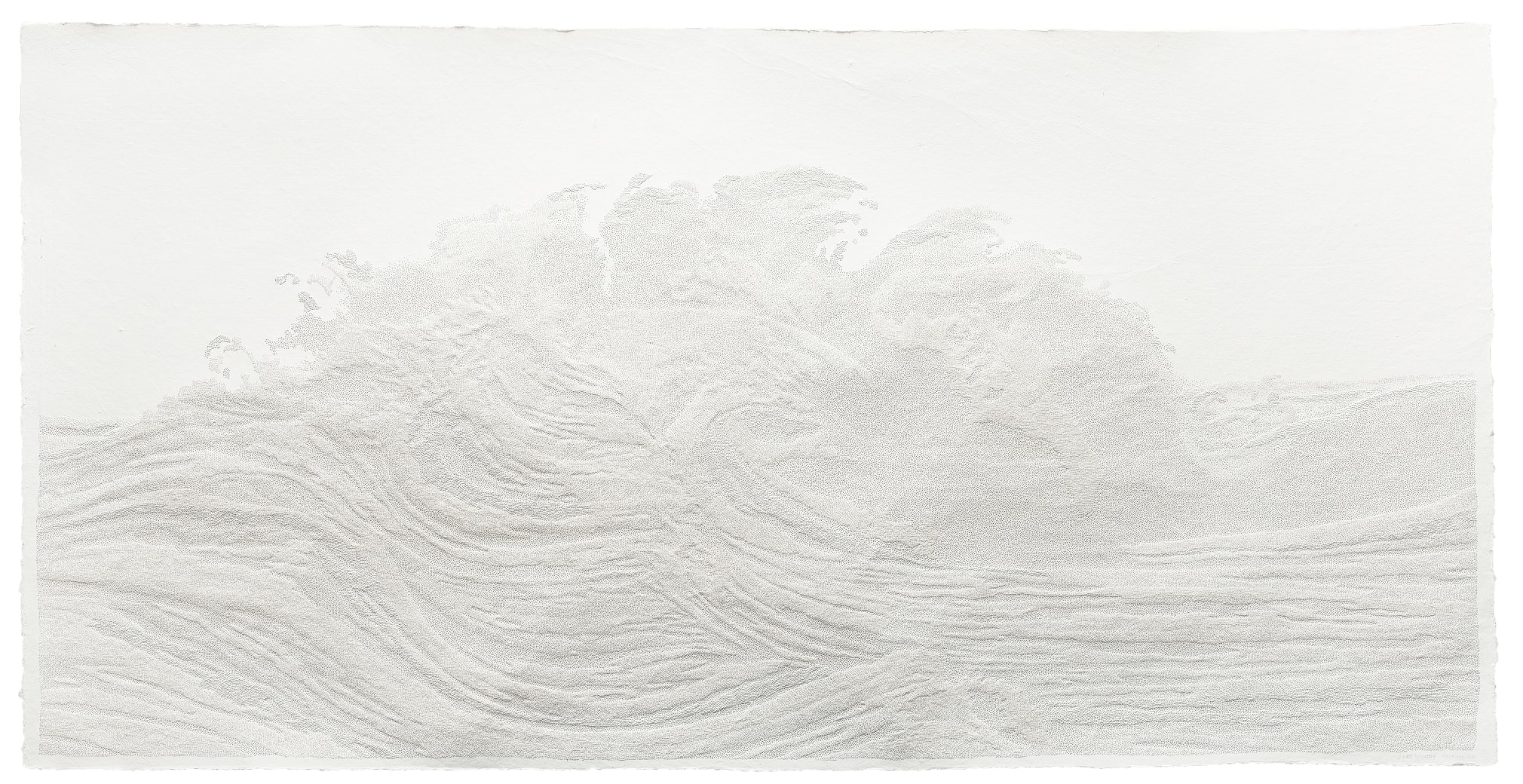

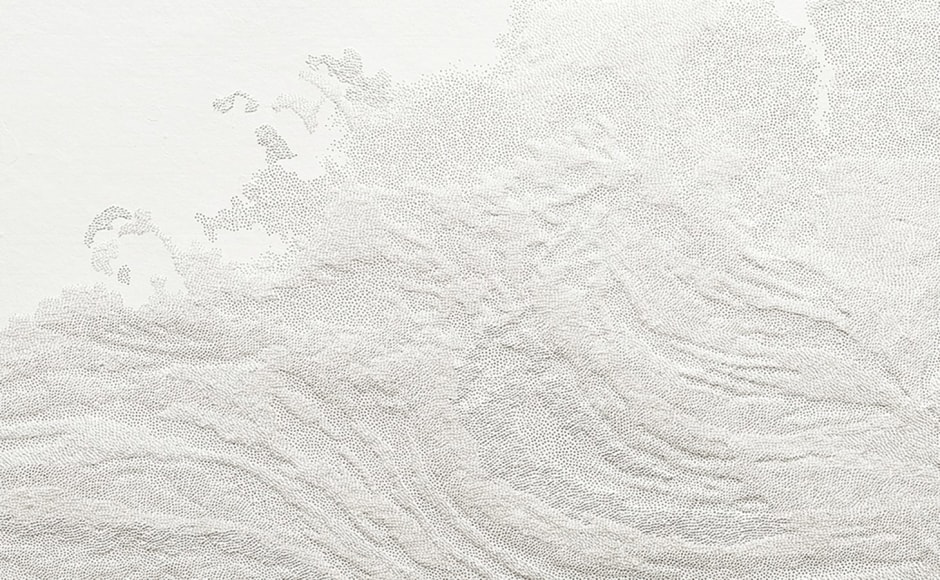

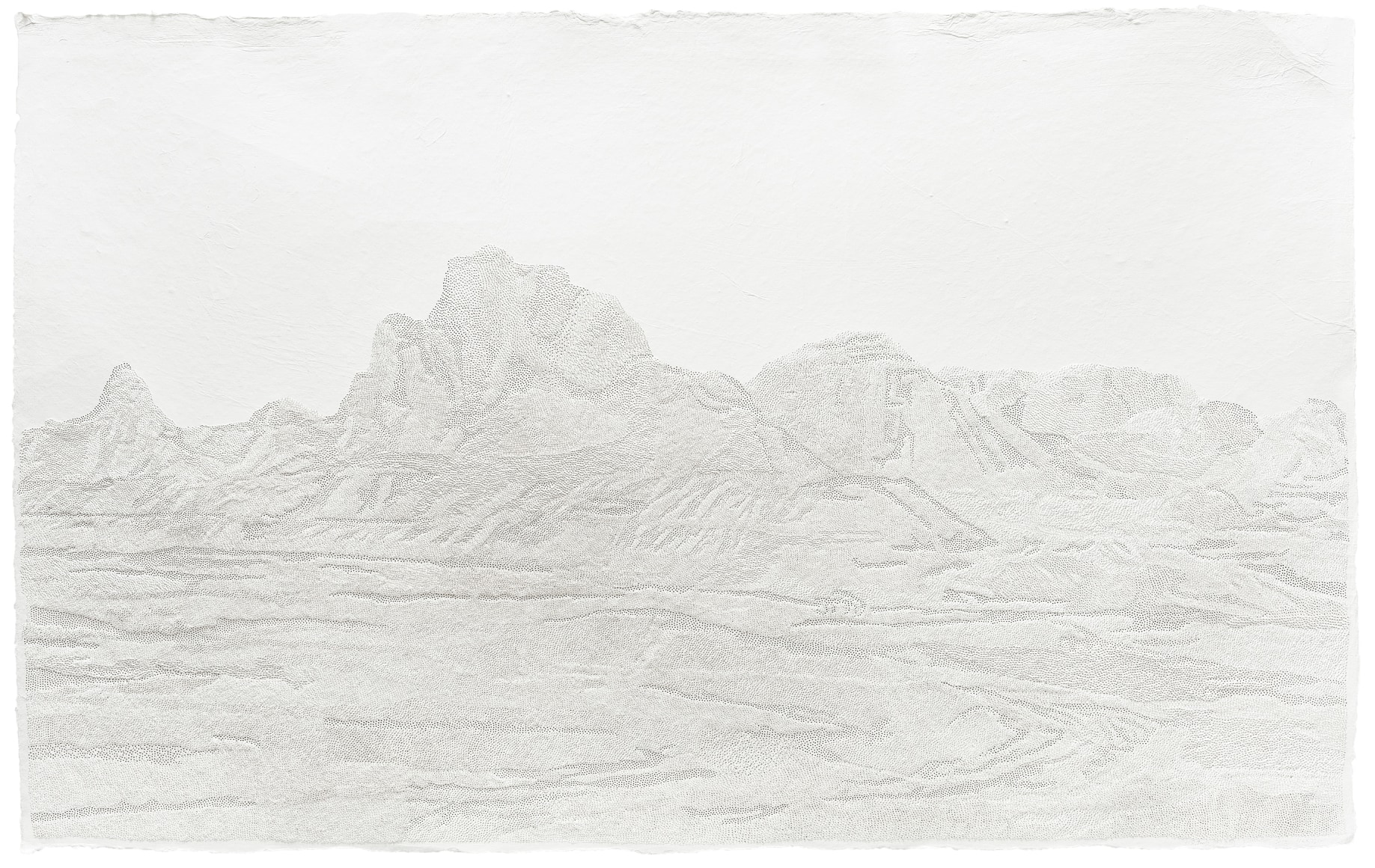

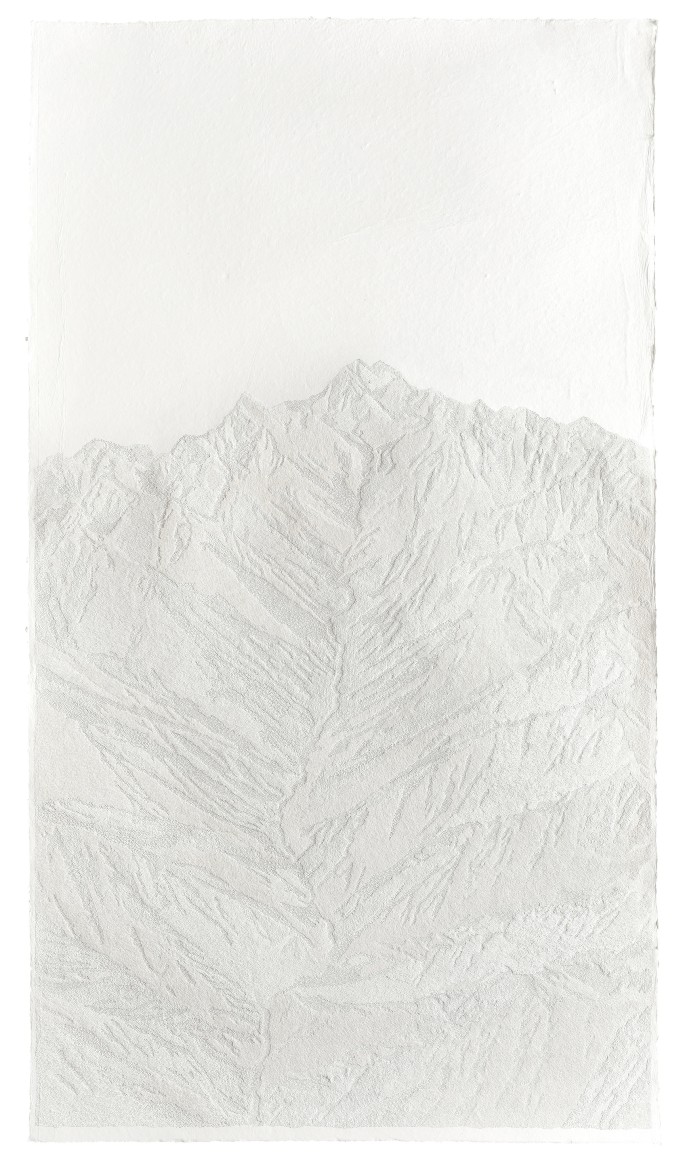

Likewise the subject matter that she generally favors – mountains, rocks, water – has a long history in Chinese visual culture although everything else about these dazzlingly white sheets of paper, many of them large in scale, is unconventional and unanticipated. “In the end,” she has written, “I chose handmade Xuan paper to be my primary medium and decided to use needles to pierce holes in the paper to form images.”

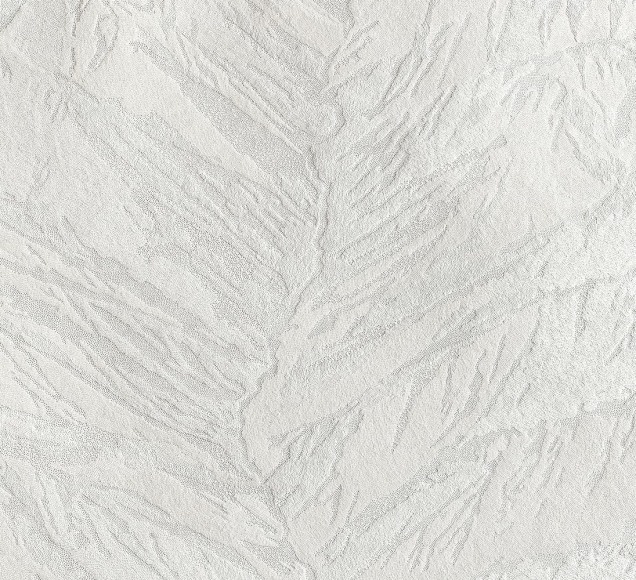

Fu Xiaotong is adamant in her refusal to mask the surface of the organic Xuan paper she so admires, choosing to reveal its qualities through excavating its surface with a needle hundreds of thousands of times. Over the last five years she has evolved a “language of the needle” consisting of five different ways of approaching the surface of the paper. Early on in the development of this technique, she only perforated the surface of the paper from directly above, but now she also approaches it from the reverse side and at an angle from the left and from the right. Each work is preceded by a detailed preliminary study in which the subject matter is broken down into a complex network of interlocking parts numbered one through five. By now she has such control over the use of the needle that she is able to visualize how different combinations of directional strokes result in convincing representations of rocks and water. Seen from close-up, the texture of her paper works resembles textiles or tapestries in the intricate interlocking of the multiple units of directional needle holes.

Tempting as it is to associate Fu’s use of the needle as a sophisticated update of traditional “women’s work,” it soon becomes apparent that her labor-intensive practice has as much in common with certain types of conceptually-based work. In choosing to title her works according to the number of pinpricks required – from 200,000 or so for a relatively small work to several million for a medium-size one – she calls attention to the procedure through which they are made, detracting from their apparent relationship to the culture-laden and possibly moribund tradition of Shan Shui (traditional Chinese landscape painting). Through her obsessive daily practice, she revitalizes a theme that has been so important throughout Chinese history.